Aidan was 18 months old when we first had our doubts dispelled, our suspicions confirmed, and our whispered concerns echoed aloud by a highly experienced paediatric neurologist.

We’d asked his wonderful paediatrician, Professor Claudia Gray, for a referral to Dr Birgit Schlegel at his 12-months wellness check, and then waited for 6 months on her waiting list for his evaluation. We were a jumble of nerves leading up to this first official assessment, but also desperate for some clarity. At 12 months old, Aidan had begun to regress. It felt as though he was losing skills by the day. He had lost the only three words he ever said, couldn’t walk independently yet, his eye contact was minimal, his hearing seemed impaired, and he was becoming super picky with solid foods. He had never slept well, but we were getting even less sleep than usual. We’d also experienced a move from unhappy wailing, to tantrums, to meltdowns, and were feeling uneasy about his increasing episodes of dysregulation.

I didn’t get a wink of sleep the night before our morning appointment. My mind was racing and I was mentally listing all the developments of the last few months and what their possible implications could be. Monty had been the first one of us to say the word “autism” – when Aidan was just 6 months old. I remember being furious that he’d suggest it and hastily sweeping it under the rug: “He’s just delayed. Maybe it’s a learning difficulty.” But as time went on and everything seemed to be worsening across the board, particularly his sensitivities and behaviours, I was forced to admit to myself that Aidan did check some of the boxes. More than one. A lot more than one. Most of them, actually. But I was determined to go in with an open mind and heart, cleared of all the noise and emotional clutter, to hear what Dr Schlegel had to say.

The day dawned grey and overcast as we got our precious, beautiful, miracle rainbow baby ready to go in. Aidan had had a bad night’s sleep and was a little moody, and that mood only darkened as we pulled in. At 8 months old, Aidan had been briefly hospitalised with a severe virus and dehydration. The week we’d spent in the children’s ward had so traumatised him, that he was extremely fearful of hospitals and doctor’s rooms. That fear is present and challenging to this very day! As soon as we parked the car, he went into mega meltdown, and we carried him screaming down endless long corridors to meet the neurologist. I remember saying a prayer (or three!) that this seasoned professional would be able to see past his tears and fears, and that all this drama would not affect his overall evaluation.

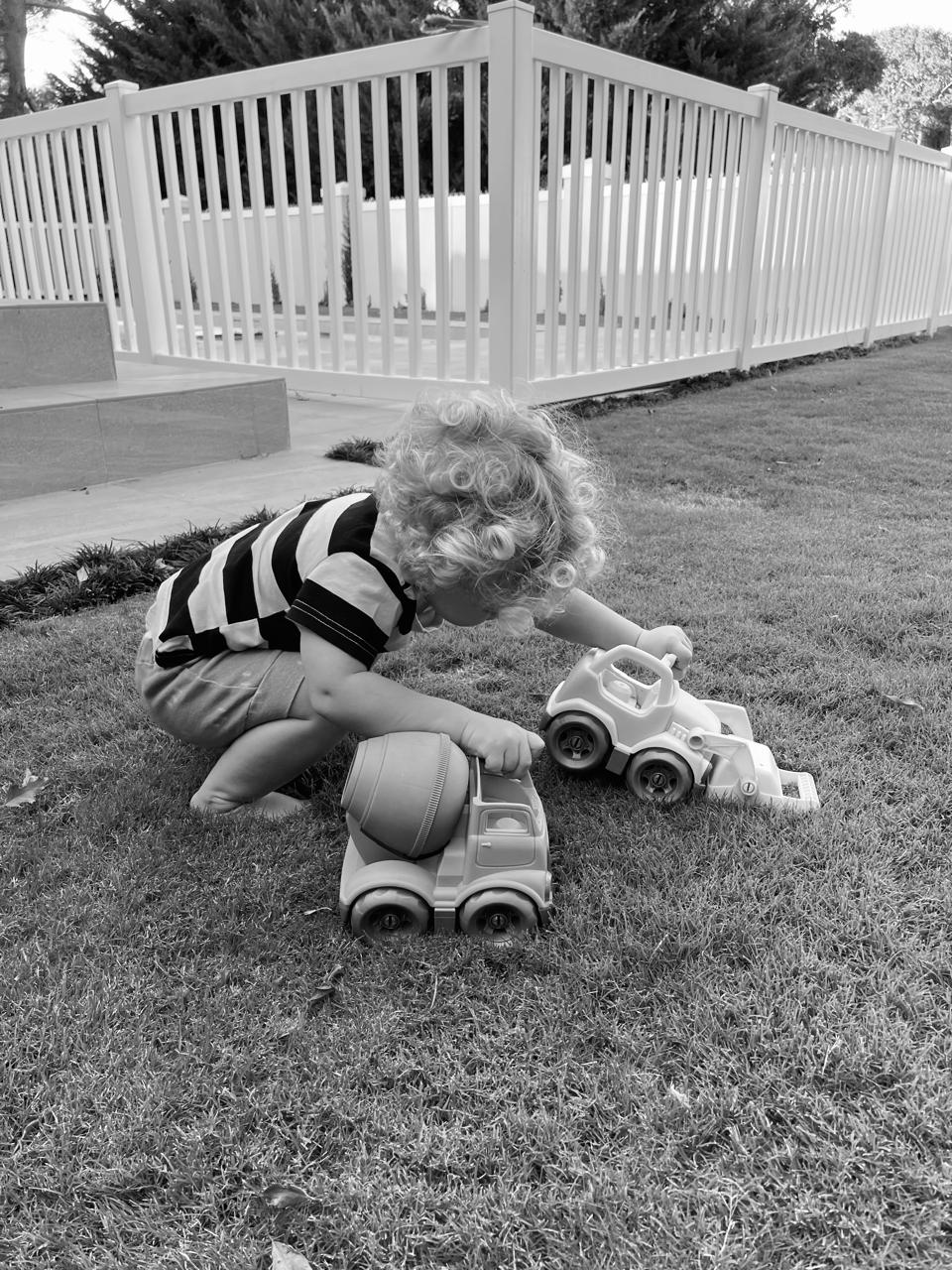

Once cajoled into her rooms, Aidan set about trying to escape as quickly as possible. We stood blocking doors until we were ready to be seen. My stress levels were pretty high at this point and I cried while I gave her his history. Dr Schlegel was a very calm and kind lady. She asked lots of great questions and told us when she was going to begin her observations. She sat casually and comfortably on the floor with Aidan and tried to spark his interest with a number of fun toys and games. Some activities had clear objectives, and I could guess at what she was looking for. But it was only once we received her report two weeks after Aidan’s appointment, that we realised she’d been assessing a lot more than we ever would have guessed at. After an hour of attempting to engage Aidan in floor time, she asked us to walk him down the corridor so she could observe his gait. I explained that he was a late walker and had only been properly mobile for four months at that point, but that didn’t seem to be what she was particularly interested in.

Back in her office, she explained that this was not a formal diagnosis, as it was too early to make one. But that she believed Aidan was “firmly on the spectrum.” She explained what the CARS system of evaluation was and told us we’d receive his score in her report. But that no matter what it was, we shouldn’t focus on it because the early intervention therapies that she was going to recommend, would likely shift it for the better. She reassured us that we’d done the right thing bringing him in as early as we had, because we had more time to make the most of what she called, “the window of opportunity.” This is the optimal time, between the ages of 2 and 4, for early intervention to be its most effective. And that was of great comfort to hear.

Aidan was quiet on the journey home, and I wondered what he’d made of it all. I so often wonder what he’s thinking and I hoped against hope, that despite his loss of words, one day, he’d be able to tell me. And as we drove past familiar landmarks, past shops we frequented, on the same route home that we’d taken to get there, I marvelled at how four little words had changed absolutely everything – “firmly on the spectrum.” Our lives, our journey, everything was inescapably altered: We were an autism family now.